Maria Alexandrovna Stepanova: Bintang Basket Profesional dan Olimpiade Rusia

Pendahuluan Maria Alexandrovna Stepanova adalah salah satu pemain basket profesional paling terkenal dari Rusia, yang…

Małgorzata Dydek: Legenda Basket Wanita dari Polandia dan Amerika Serikat

Pendahuluan Małgorzata Dydek, yang lebih dikenal dengan panggilan Margo Dydek, adalah salah satu pemain basket…

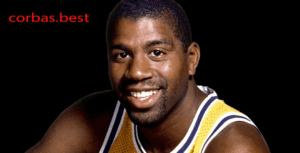

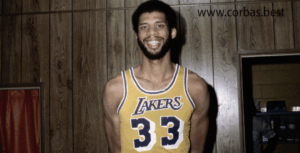

Earvin Johnson Jr.: Legenda yang Dianggap Sebagai Pemain Point Guard Terbaik Sepanjang Masa

Pendahuluan Earvin Johnson Jr Dalam dunia basket profesional, beberapa nama telah melekat sebagai legenda yang…

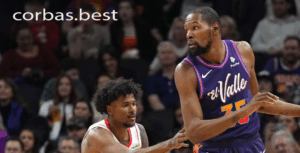

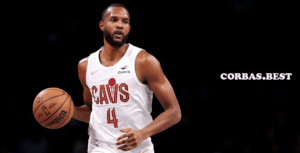

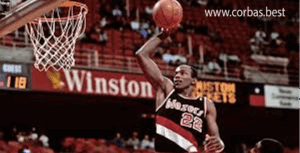

Carmelo Anthony Dipilih oleh Denver Nuggets di Tempat Ketiga pada Draft NBA 2003

Pendahukluan Carmelo Anthony, salah satu pemain paling berpengaruh dan berbakat dalam sejarah NBA, memulai perjalanan…

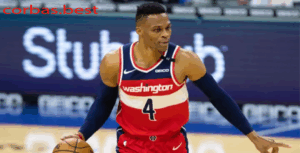

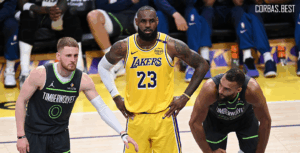

Dallas Mavericks dan Los Angeles Lakers: Meningkatkan Kompetisi dengan Luka Doncic dan Anthony Davis

Pendahuluan Dallas Mavericks dan Los Angeles Lakers Dalam dunia bola basket NBA, perdagangan pemain selalu…

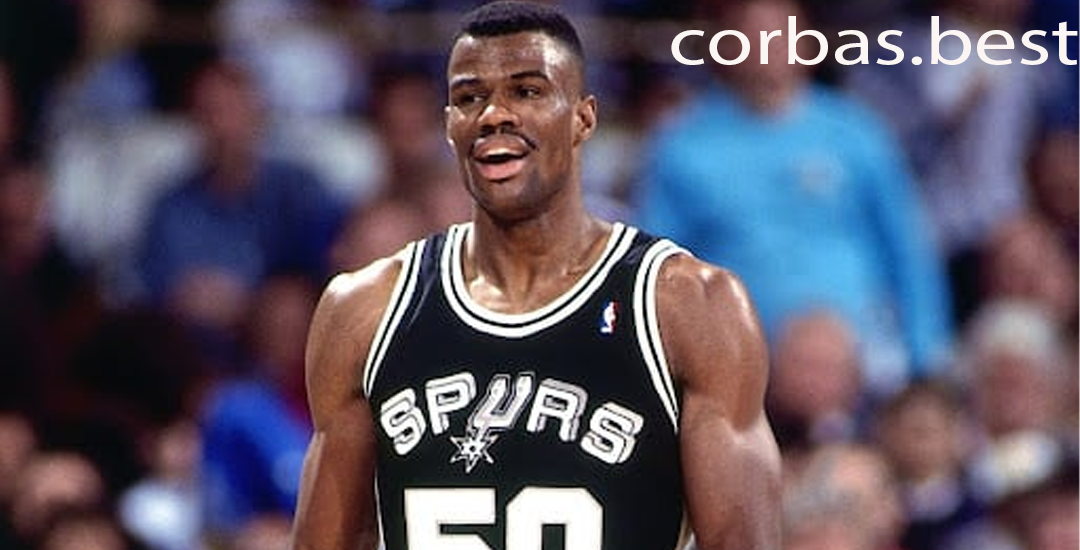

David Robinson: Legenda yang Mendalam di Hati Para Penggemar San Antonio Spurs

Pendahuluan David Robinson, yang dikenal dengan julukan "The Admiral," adalah salah satu pemain basket paling…

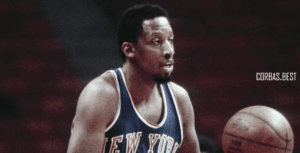

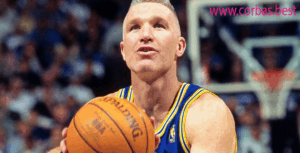

Theo Ratliff: Pemain Serba Bisa yang Dipilih oleh Detroit Pistons di Urutan ke-18 NBA Draft

Pendahuluan Theo Ratliff merupakan salah satu pemain yang dikenal karena keunggulan defensif dan kemampuannya bermain…

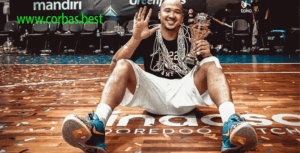

Grace Jesslyn Rasali: Pebasket Muda Berbakat dan Inspiratif dari Indonesia

Pendahuluan Grace Jesslyn Rasali Dalam dunia olahraga bola basket nasional, munculnya pemain muda berbakat dan…

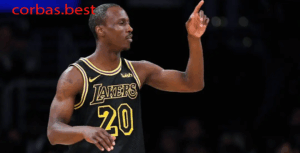

Andre Ingram: Perjalanan Inspiratif dari G-League ke NBA

Pendahuluan Andre Ingram adalah contoh nyata dari ketekunan, dedikasi, dan semangat pantang menyerah dalam dunia…

Megan Gustafson: Bintang Basket Profesional Amerika yang Menginspirasi

Pendahuluan Megan Gustafson adalah salah satu pemain basket wanita profesional yang tengah naik daun di…